Markets today are more efficient than ever. The ever-increasing speed of information transmission and constant focus on short-term returns mean that an active, long-term investment approach is more and more important if you are to distinguish yourself from the pack. In 2019, the NN IP European Sustainable Equity strategy did just that, generating an absolute return of +36% and a relative outperformance compared to its benchmark of 10%(1). This achievement is a testament to the strength of the dedicated team behind the strategy and the success of their long-term, ESG-materiality-focused approach. Hendrik-Jan Boer, who heads up Sustainable & Impact Equity Investing at NN Investment Partners, explains what caused last year’s stellar outperformance. He also explores the benefits of a value chain approach, the importance of materiality in sustainable investing, and why a long-term investment horizon pays off.

A real team effort leads to success

Even before 2019, the strategy had a solid track record of resilience in the face of adversity. “We consistently performed well despite global tensions such as the financial crisis, Brexit and Trump’s election,” says Boer. “Although the markets were on our side as equities across the board performed well, for me, the reasons are closer to home. It is largely thanks to the work we’ve been doing behind the scenes, to get the team where it needs to be.” The strategy is now run by a dedicated team of 15 people, and Boer credits much of the success to their combined efforts. “We all have the same mindset, the same criteria and objectives, and that leads to a high level of conviction in our portfolio.”

The strategy’s success also owes a lot to the team’s focus on in-depth analysis. “Before we invest in any company,” Boer explains, “we bring together all the team members to get their take on the stock; the positive factors and the potential pitfalls.” This part of the process has real implications for decision-making and portfolio construction. If opinions differ strongly or new key arguments come to light, that can be a reason to reassess or even not to invest. “Ultimately, we want to create a portfolio that the whole team feels comfortable with.”

The benefits of a long-term perspective

The first step in the investment process is to apply a binary ESG data screening that leads to the exclusion of certain companies from our investment universe. “For example, we exclude several activities at industry level – weapons, gambling, tobacco – as well as companies that have a track record of behaving very poorly in the execution of their business processes.” This can range from serious environmental pollution to a negative track record on human capital issues or major corporate governance controversies. The team also screens out companies with very negative ESG momentum. “But all this only reduces our global universe from 15,000 to 11,000 stocks, so ESG screening still leaves an immense investable universe, contrary to what many often think.”

After this initial screening, the team uses the HOLT® system for an initial financial screening of its starting universe. “Why use HOLT? First of all it gives us an enormous universe, far beyond the usual benchmark names, and a lot of room to play with – having a wider scope is always beneficial. Secondly, this tool analyses companies in a highly consistent and rigorous way.” Each company has its own accounting standards and its own methods of dealing with pension liabilities, depreciating goodwill, lease arrangements and so on, which can make comparisons difficult. As Boer explains, the HOLT tool adjusts for these discrepancies, so we can make apples-to-apples comparisons.

Furthermore, the HOLT methodology offers a powerful lens for looking at the long term, which is what matters to Boer and his team. “We invest for sustainability, but this should be naturally linked to corporate business models and their long-term trends. But also from an investment perspective, we have all had bad experiences from taking too short-term a view on what makes a stock go up.” At this point, financial markets are so efficient and fast that everyone works with the same news and the latest corporate data. As a result, Boer explains, most of this is already factored into the consensus view for the first two years out.

“The HOLT tool, on the other hand, uses discounted cash-flow models that better reflect and resonate with a long-term perspective. We look at the cash-flow return on invested capital – the cash at hand that can be invested in new assets or allocated to investors – and at how the company uses it.” This return, in combination with the asset growth, determines the company’s economic profit. The most important metric to the sustainable equity team. “Ultimately, we prefer to look at a longer-term horizon, say five years. Then we can evaluate big societal changes like the energy transition or new trends in consumption and communication, and identify major deviations between our expectations and the market’s perception.”

Portfolio preferences: assessing the value chain

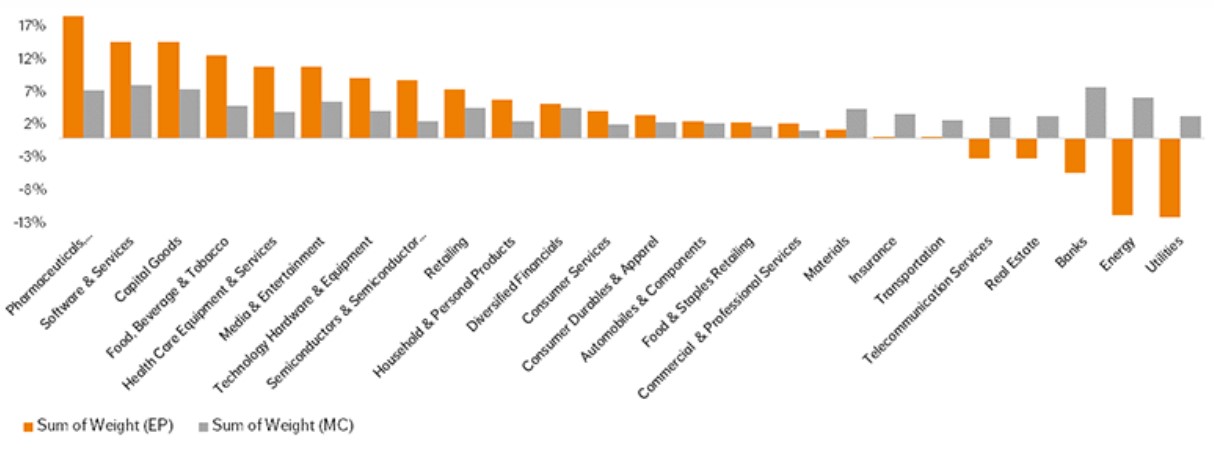

When it comes to selecting the best investment opportunities for the portfolio, the team initially looks from an industry perspective to determine which areas structurally offer the best profitability. “Most of the time, and academic research also confirms this, returns are determined more by the industry a company is in than by the qualities of the company itself,” says Boer. If an industry performs badly, this is often indicative of structural issues such as the commoditisation of its products and services that has led to intense competition, low barriers to entry, or changing consumer behaviour that favours alternative products. “We prefer to avoid structurally unprofitable and low-profit sectors that barely make their cost of capital, such as banks, chemicals, utilities or even real estate. There are sometimes exceptions – you might find a successful niche materials firm, for example. But overall we prefer industries with the capacity to generate higher average economic profits.”

The team has value chain analysts rather than sector analysts, which makes for a much broader range of coverage. “In the energy value chain, for example, we include solar and wind as well as companies that produce components for these industries. These companies are typically in the industrials or IT segments rather than in energy or utilities.” On a similar note, the team’s financials value chain analyst follows very few banks because their returns are very low. “But we do see strength in companies that create the network and support the necessary payment operations – like Visa, Mastercard, Adyen* – or those involved in data processing or creation, such as Moody’s or stock exchanges. Data is arguably the new fuel of the world.”

When it comes to the selection of individual stocks on economic grounds, the team first excludes any companies that make insufficient returns relative to their cost of capital. “After that, we look for companies that are not only making good returns but also demonstrate strong asset, or capital, growth. We therefore also look at where in the life cycle each company is: is it in the startup phase, the growth phase, the easy cash flow generation phase, or is it maturing and coming to the end of its life cycle?” This process reduces the universe from 11,000 names to around 350 for the global portfolio, which is the universe that the team analyses very closely. “This is also where we analyse ESG integration in the business models in much more detail, and where we want to see our investment opportunities moving in the right direction and showing the right behavior.”

Figure 1: Which industries generate economic profit?

MCSCI World Index misrespresentation: Industry Group Economic Profit vs. Market Cap weights

Source: NN Investment Partners, MSCI and HOLT

This analysis is very rigorous and has a long-term focus. “We don’t need to fully screen the universe every month, because the long-term metrics we look at do not change that rapidly. Sometimes it’s more a case of slowly becoming aware of a new trend and wondering what impact this could have on our holdings and favoured industries. We might then take another look to see if anything new affects our criteria.” The team then constructs the total portfolio with an eye to diversifying across the different value chains. “We believe that each stock should have an equal chance to contribute to alpha, and so we make sure our portfolio characteristics are not too tilted in favour of any one single name.”

The overall portfolio does over- and underweight certain sectors, within the confines of our sector limits. It overweights IT, healthcare, and certain consumer sectors, and clearly underweights energy and utilities. But as Boer explains, this risk is highly controlled. “What’s important is how our portfolio behaves versus the benchmark. We assess this by looking at our tracking error composition, how our portfolio behaves in different scenarios, such as a major market draw-down or a spike in interest rates. We find ultimately that we are so diversified that even a very strong and unexpected market move is unlikely to put a dent in our relative performance.”

Materiality matters

With regard to sustainability issues, material factors are what’s important, and these differ significantly between sectors. “Take UnitedHealth[2], a US healthcare insurance provider, for example,” explains Boer. “For a company like this, the most important sustainable topics don’t relate to the environment or carbon footprint. Privacy of client data, reliability, access to affordable healthcare, working for the greater good in society are more relevant factors. And since it’s a healthcare company, it shouldn’t seek to profit too much from its clients.”

for companies involved in new energy production or technology, the environment is a crucial concern. But even then, it’s not a simple equation. “Companies like Microsoft[2] use massive amounts of energy. But by moving everything to cloud servers, storage can become very energy-efficient, as it means using one cloud machine for multiple clients. This leads to very high capacity utilisation. In combination with Microsoft’s ambition to source all their energy needs sustainably in a few years, this represents an enormous step towards a smaller carbon footprint.” For Boer, sustainability analysis means looking at the subtleties, not just taking things at face value.

At the end of the day, the team aims to link a company’s sustainable behaviour to its core activities and its potential for generating long-term returns. One example here is Neste[2], a biofuel producer that converts leftover fats from a variety of sources into airline fuel. “In turnover terms this business line represents only a small part of the company’s revenues, but it already represents the majority of its profit,” Boer says. “Neste also enjoys pricing power because the amount of biofuel used per liter of kerosene is still small, but it’s worth a lot to airlines because it helps them improve their sustainability profile and comply with ever more stringent expectations. And because of this pricing power, Neste now consistently generates healthy returns.”

Ultimately, each company in the portfolio has a different materiality framework, so each one requires close analysis. “Of course there are overarching portfolio characteristics – in terms of carbon footprints and certain governance metrics, for example – but every story is different with its own specific elements that contribute to sustainability and returns.”

Sustainability is not always obvious

It is not always clear where the most sustainable investing options are. This can be particularly true for social concerns, where sustainable contributions are often harder to quantify than environmental aspects like a company’s carbon footprint. A good example is Match[2], a holding in the Global Sustainable Equity portfolio. This company owns dating platform Tinder, among other things. “Many people question the sustainability of a company like this, but it has done a great deal for people in social terms. We all have friends and colleagues or know people who have difficulty finding a partner that have benefited hugely from using these platforms. The social benefits of reducing loneliness are massive and unquantifiable.”

The global portfolio also owns Amazon[2], a company that has frequently been challenged on both social and environmental aspects. “We receive a lot of questions about its carbon footprint, but the calculations show that all else being equal, centralised distribution means that ordering items online is more efficient. This leads to a much smaller carbon footprint than everybody driving around to do their shopping.” As for social aspects, the team has actively engaged with Amazon on the rights of warehouse workers, among other things. “We have seen positive changes. Last year they were among the few companies that substantially increased minimum pay for their employees.” But as Boer points out, improving these types of situation in relatively new and young industries will also require action from governments and regulators. “All of these are issues that we need to work on together – investors in their engagement with companies, but also consumers, regulators, and the companies themselves.”

For Boer, “real” ESG integration is not just applying ESG scores from external providers. He views this as a very simple and basic filter that no longer provides alpha. “Why? Because the rest of the market also has access, and there’s often no logical economic link between the methodology of these scores and a company’s true business activities. What we do is focus on materiality, which requires close engagement with companies.” Sometimes, he says, looking closely at a company can lead to new insights that the market isn’t yet aware of. “I don’t mean non-public information, but information that wasn’t included in the company’s sustainability report, for example, perhaps because they don’t yet have one.”

Bakkafrost[2], a sustainable salmon producer, is a key example. The firm’s low Sustainalytics rating largely stems from its lack of sustainability reporting. “We think that’s ridiculous. They’re raising salmon in a sustainable way, without antibiotics, in a pollution-free environment.” From conversations with the company, the sustainable equity team has also learned that Bakkafrost is creating a biogas terminal to process its remaining waste, and will also be publishing a sustainability report. “So from that direct contact, we know their Sustainalytics ESG score will probably improve.”

Relatively small companies are also more likely to face low ESG ratings. They do not have the resources of multinationals, with 10-20 people on hand to write their sustainability reports. “But this doesn’t reflect on the quality of what the mid-caps are doing.” SolarEdge[2], a producer of inverters and optimisers for solar panels, is a good example. Based on its technology and skill, SolarEdge is expected to become the preferred partner of utilities for industrial solar installations. This segment is set to accelerate, as the current growth rate of solar will need to increase three- or fourfold to attain the 2050 net zero emissions targets. “Still, SolarEdge remains a relatively small company without the capacity to create an extensive annual sustainability report. Because they don’t produce it, they don’t tick that box and therefore receive a lower rating.”

Conversely, many oil companies have relatively high ESG ratings. As Boer explains, this counterintuitive outcome is the disadvantage of so-called sector neutrality, which means taking the leaders from each industry. “In the end you’re still investing in an oil company, which is highly pollutive. We draw the line here. We prefer to opt for innovation.” In the past, many investors viewed the whole exclusion of the oil sector as a dangerous investment approach because if the oil price rises, oil stocks will also go up. “But these days, renewable energy sources are so efficient that when the oil price rises, it becomes economically even more sane to choose solar.”

Looking to the future

As companies and markets move towards environmentally-friendly policies, the value of an actively sustainable approach may appear to be diminishing. Boer admits that the market is certainly evolving. “We all know that we’re on a downward path, environmentally speaking, and we need to improve our sustainability. But although the benchmark’s ESG scores have increased, has the benchmark itself become more sustainable? I don’t think so.” Many investors and companies are talking the talk, but he contends that much of this is compliance with some box-ticking, mostly focused on governance and less on the environment. “Furthermore, many people are investing in passive funds. Funds like these are not able to be truly sustainable like we are.”

For Boer, it is shocking that many analysts fail to make a connection between the major issues facing the world today and the future of the firms they follow. “But over decades, the most successful investors are those who, like us, focus on long-lasting quality. That includes economic quality but also quality linked to material ESG concerns or opportunities.” Investors like these, he contends, have a very specific, dedicated way of doing research, and that applies both to smaller boutiques and some of the more famous individual top investors. “And still, the majority of investors are not paying attention to this. They want something that will do well immediately.”

This is especially evident from conversations with clients, who are often focused on problems that have a temporary impact. “But with our long-term focus, we’re looking at the situation five or seven years down the line. The coronavirus is creating huge waves in today’s markets, but it’s impossible to extrapolate from this what markets will look like in five years.” As Boer explains, the companies in which they invest are so high-quality and resilient that they should still outperform their rivals in the long run. “So with that in mind, why would we step out now?”

Ultimately, Boer says, the most important factor driving long-term returns is the underlying earnings current. High quality leads to a stronger underlying earnings current, and in turn to long-term stock market success. “If you have a company that can internally finance its high growth and continues to generate excellent cash-flow returns, you get a fantastic earnings compounding effect. The market cannot ignore this and share prices inevitably have to follow. All the rest is random noise.”

[1] Benchmark: MSCI Europe (Net)

[2] For illustration purposes only. Company name, explanation and arguments are given as an example and do not represent any recommendation to buy, hold or sell the stock.